From the depths of the infostructure emerges an image: a girl wearing a necklace of needle-like steel spikes wrapped around her throat. The post is captioned with a tutorial on how to wear the necklace safely, that is, without piercing your arteries.

I remember the exact moment I wanted to attempt theorizing the revival of medieval aesthetics. It was the fall of 2022; I was at my grandpa’s house in the countryside, sitting by the fireplace and reading The Coming of Neo-Feudalism by Joel Kotkin—a book I had mistakenly double-ordered online (from Amazon). The air was cold and crisp, the sky quiet and full of stars—one night, they aligned in a perfectly straight line and freaked the fuck out of me.

There was I, unwittingly staring at a Starlink battery slowly cutting through the sky, suddenly reminded of how far I am from those who wield power, the tech monarchs - a pauper in contrast, a simpleton from Eastern Europe, trying to keep warm by the fire. The book “hit hard”, like a family intervention. The ugly patterns resurfaced.

Its premise is rooted in an economic analysis of how today’s societal structure in the West—primarily in the U.S.—increasingly mirrors that of medieval Europe. Kotkin identifies three emerging classes that parallel feudal society:

The Tech Oligarchs – a small group of billionaires wielding immense wealth and power. The Clerisy – academics and media professionals who shape narratives and policies. The New Serfs – the downwardly mobile middle class, precariously struggling with stagnant wages, unaffordable housing, and limited opportunities.

These reflect the concentration of wealth and land ownership becoming a tightening circle, contracting around fewer and fewer hands. Wealth is becoming more inheritable than earned. Even the seemingly accessible educational path, the rise to Clerisy - at least in Europe - is a mix of luck, wealth, charisma, connections, and identity, all of which slowly elevate a person into an icon of contemporary discourse. Most of us lack one or more of these. Most of us are doomed to a precarious life.

And then the plague comes—a grotesquely medieval symptom. The early 2020s, during Covid, were not about slowing down and reconnecting with the local; they were about the loss of innocence and decline of the political drive. The Great Reset conspiracy posited a political and economic restructuring of the world, but more than that, it was a normative restructuring, forcing a reevaluation of our place in locality and what we do about it. The pandemic, in its suddenness, threw us into a fever dream of lockdown, whether it was family time-out-of-time or getting hammered with your besties; that suddenness still lingers, its psychological and cultural effects wavering between too obvious to mention and too early to tell. The fever dream lasted a solid three months. We woke up confused and horny.

Most vegetarians I knew started eating meat during or shortly after Covid. I no longer see people ashamed of buying bottled water, disposable vapes, or clothes from Temu. Zillennials want kids again. The ecological anxiety over 2050—the slow, creeping fear of planetary collapse—was replaced by something else, by an ex nihilo disaster. The distant specter of generational ruin was overtaken by the immediate terror of sudden death.

The Aesthetics of Neo-Decadence

It is impossible to theorize a historical moment while living through it, but it is always possible to look around and complain. The winter is too cold, the summer is too hot. A sweet lyre melody drifts through the air as Rome burns, too sweet. The invisible hand turns down the stove, reduces the fire to a simmer, and the Rome-pot cooks slowly with a heap of Roman frogs inside.

The Spectacle is reaching self-consciousness, settling into a post-Fisherian acceptance of the realism of the end times, the death of political imagination. There is no more thinking to be done—only restless observation as global politics unfold within a system designed to elevate sociopaths to tech-moguls. Unless, of course, you take action into your own hands, driven by a brilliant idea. But you have so much to lose!

Singular acts of strong, political action explode like a gunshot in a cathedral—brief, deafening, then swallowed by the corners and spandrels of a fragmented news cycle. And from this quietness a new form of decadence grows—suspended between celebration and mourning, marinated in the lack of agency and the beauty of endless consumption.

It’s anti-apocalyptic, in a way. Things will continue, and continue, and continue. You’ll never have the satisfaction of a cleansing end of days. Ugliness, stupidity, grotesque cliches, commercial sentimentality: all of them will keep being rewarded, as they always have been. Things will just keep getting dirtier, so you might as well enjoy it; even find a genius in enjoying it.1

The call to enjoy and a Coca Cola bottle. And the girl you fell in love with and the nice clothes you bought. And a new tattoo that healed badly but it doesn’t matter.

We could ask why everything became so cute and why everything became so spiky at the same time. Viewing Covid as a brief extinction scare, we can see two parallel ways of dealing with trauma. One embraces fun, cute, and colorful energy after an extended period of isolation2. The other taps into the hyperreality of the dark, obscure, occult, and violent. Visually, it’s the choice between round and spiky, between friendly and aggressive. In accessories, it’s choosing between Sanrio characters or a raw steel thorned heart, between fluffy Kirby and a necklace you really wouldn’t want to trip on the stairs in. I know people who mix both, maybe because they contain multitudes, or maybe because they’re just stylistically confused.

Both are ways of coping, and both are ways of being—whether by embracing life or embracing death, by appearing approachable or untouchable, by choosing to be the nice guy or the bad boy. Since 2020, culture has progressively exposed us to more and more cringe—whether in the silliness of TikTok or in performative political engagement. Some chose to escape the goofy domain of showmanship for an apparitional stoicism, for going anti-Camp.

The visual trajectory of Drain Gang’s Bladee in recent years follows a progression from cute and silly into dark, with undertones of godposting. The same with Playboi Carti’s evolution from hypebeast to a rockstar to a mysterious, detached vampyr cloaked in black folds, both sprouting a wave of fan followers. The kids will follow and eventually be alright. What’s interesting is the wave of a recent shift from cuteness to darkness in the performative creation of self—and the lifestyle it entails. And whether we can speak of a new aesthetic emerging alongside the custom tattoo boom.

The Dandy

All of the mentioned above can be placed as the aftermath of the infamous vibe shift3 of 2022, a subject too overdone to mention in depth, which signalled the introduction of indie sleaze and the slow decline of millenials’ dominance in culture. Y2K can be endlessly replayed in fashion, but something deeper is growing beneath the surface - the rise of hyper-individualism, brought on by post-Covid trauma, that has created a desperate need for self-expression in a society that no longer ‘works’ for you.

There is a figure that has historically risen during the end times. The Dandy, originally just a well-dressed man, has been conceptualized more broadly as a lifestyle choice synonymous with decadence and the fetishization of surface. A Dandy is a mix of gentlemanly, rebellious, androgynous, aristocratically pretentious, theatrical and meticulously styled. A pursuit of wit, pleasure, and extravagance. Think Salvador Dalí, but also think Lil Uzi Vert.

A Dandy doesn’t have to be a clinical narcissist, but must possess narcissistic traits—just as anyone participating in the specular circulation of images does. The prophecies of Christopher Lasch have fulfilled themselves in the modern age, where both your real life and internet persona become commodities in the social market—an arena for the presentation of self in everyday life. Which means that, unless your ambitions remain confined to a cozy corporate job, a tight-knit group of childhood friends, and a single-digit body count, you’ll likely have to market your image in the digital world.

Independence makes the Dandy. […] Dandyism achieves charisma by the codification of costume and taste, the cultivation of habits of speech reflective of continence and power, and, in many cases, the suggestions of a queer substrate to masculine performance.4

Dandy is the appearance of aristocracy despite middle-class background, the ‘medium is the message’ embodied, a mix of the Apollonian and the Dionysian. The prerequisite for a traditional dandy is a certain level of popularity, however modest, a base of onlookers, a vivid social life, and a creative practice. For the dandy-socialite, the challenge lies in navigating a dialectical path between the two.

You cannot maintain two destinies, that of the fool or the intemperate and that of the wise and the temperate. You cannot keep up a nightlife and amount to anything in the day. You cannot indulge in those foods and liquors that destroy the physique and still hope to have a physique that functions with the minimum of destruction to itself. A candle burnt at both ends may shed a brighter light, but the darkness that follows is for a longer time.5

The dandizettes like Coco Chanel, George Sand, or Tilda Swinton write their own stories the way they would write their characters. As Len Gutkin puts it, dandyism is not possessive but identificatory. You don’t want to own the protagonist of your daydreams—you want to be them. Today, we would call it main character syndrome.

The dandy emerges wherever economic and cultural conditions allow for both joy in consumption and the freedom to shape one’s own identity, the freedom of cultural experimentation, degree of decadence and a retreat from the political. Inb4: All times are political, but some are more locally peaceful. We speak of German dandies in the 1920s, and then only in the 1990s. The real measure is one of magnitude—to what extent, with the quiet approval of society, can you fearlessly develop a persona synonymous with your aesthetic ideals?

Dandies could have been hipsters, twee girls, or McBling glamour chicks, fully embodying their cultural moment. They are all a part of the dominant social class, as it is expensive to live a fully dandiacal life. Yet they emerge only when there is enough self-consciousness to critically examine the society they live in and opt out of the status quo, turning their lives into an art form, a meticulously curated self.

We are living in an era of neo-decadence, manifesting as an appreciation for the beauty of consumption and performance—both intrinsic to neoliberalism or its technofeudal mutations. This attitude is indefensible on moral grounds, yet so many of us embrace it. I cannot blame anyone for giving up on changing the world. I also cannot fully admire those who truly attempt it.

The shift in consciousness that Covid inflicted is a mix of a “too big to fail” understanding of the substructure with complete immersion in the superstructure. We speak of ‘vibes‘ and ‘memes‘ instead of facts and opinions6. It has resulted in a feeling of alienation—old as the sun itself, scorching the soil of the first feudal field.

It seems like everything is falling apart as we look from the past to the future. […] The solution to our discouraging present feels out of reach […].7

What a dandy does is ‘take that alienation and turn it into a badge of style and honor’. Before Covid, an educational barrier—the factor of cultural capital, to invoke the immortal Bourdieu—separated academia from the flamboyant lifestyle of the dandy. There was a deep-rooted disdain for luxury brands and for an apolitical, nonchalant lifestyle defined by overconsumption and its environmental consequences. That separation was normative, resulting in contempt for excessive indulgence as reckless, a sign of complicity in a system destined to collapse.

Over Covid, this slowly changed, shifted into a more ethically promiscuous narrative. Display was once again coronated, accelerated by the warp-speed of social media. The disillusionment brought on by the pandemic created a fertile ground for a contemporary, mutated type of dandy to emerge, a figure submerged in a fantasy world of their own. The resurgence of massive Y2K nostalgia marks not just a return to its aesthetics, but to its innocence—a longing for a world that never truly existed. Dandyism, in this context, is a trauma response to Covid, but also a shift from morality to aesthetics in the pressure to signal your virtue.

New archetypes and aesthetic trends surface daily, but all of them tap into a deeper social need—one that dandyism, I believe, represents as a whole. The dandy is not someone who simply goes out—they make an appearance. Fashion, mannerisms, and the way of being take precedence, whether in real life or through the carefully constructed presence of an Instagram feed.

At its core, dandyism is an intrinsic need to be a star—to steal the spotlight, even within a niche, alternative group. It has to stem from a degree of popularity, a wide spectrum of influencership, even if you aesthetically rule a small kingdom of your village. In an era so deeply fixated on self-presentation, accelerated and fossilized by social media, to speak of the dandy becomes increasingly accurate.

If living through fin de siècle has become the status quo, then the classic dandy inevitably undergoes transformation. Just as with the division between cute and obscure, there is a spectrum of desired effects embodied by the dandy. Some abandon innocence and joy entirely. They reach for the dark, the harsh and the austere—but indulge in godposting and religious themes. They quiet down. They space out. The detachment is no longer playful, because there is nothing to celebrate. Parties and people become exhausting. The new task is to focus on life’s simple aspects. The dandy turns dark and solemn on the surface, losing their wit and flamboyance in favor of the most stoic ambition—the pursuit of a humble life.

Yet these ambitions clash with the dandiacal need to impress. Out of this tension arises a distinction—not just between joyful and sorrowful neo-decadence, but between their aesthetic implications.

Joyful neo-decadence revels in consumption, embracing the eerie beauty of capitalism and the silliness and playfulness in self-creation.

Sorrowful neo-decadence severs ties with sincere market participation, favoring privacy, mystery, and introversion in its engagement with the audience.

If there is an internal struggle, it is no longer the one Coco Chanel spoke of. It is no longer about how to live freely - but about how to find space for humility within a life of formal excess. This struggle weighs heaviest on those most tormented by the COVID scare.

The Sad Dandy

Being a doomer is a temporary state of mind, not a lifestyle choice. The aesthetics of “I need a lobotomy” are not sustainable in the long run. If tortured souls have undergone cultural therapy, it has been guided by their relationship to knowledge. The aesthetic progression from doomerism leads either toward dark academia-adjacent aesthetics or toward a darker, sadder dandyism. The difference lies in the domain of meaning and the meta-perspective on its transmission.

Dark academia and its branches find solace in learning and refuge in beauty and wisdom created introspectively. The relationship with art is one of perception, of looking at it. Dandies, on the other hand, do not want to look, nor do they want to be seen looking—hence the frequent use of shades. They want to be looked at. Theirs is a lifestyle elevated to an art piece. If academia is the walking curatorial text, the dandy is the artwork itself. Sad dandyism mirrors classic dandyism in its response to the loss of meaning, both being rooted in decadence, but it appreciates that decadence in a quiet way. It is mute. Their refusal to speak is not just a personal crisis but a rejection of the Symbolic Order i.e the modern over-expressiveness. Think Elisabet from Persona (1966).

If the happy, contemporary dandy is silly-coded and cringe, the sad dandy cuts off all connections to it. The energy of cocaine versus the energy of weed. Their sadness is not only rooted in alienation but also in the aloof aesthetics of sadness itself. Yung Lean, originator of the Sad Boys crew, declares that “the party is over” in a recent interview. He reminisces on his sobriety, seeking God and calls for the romanticization of life’s small moments. According to the neo-decadence movement, beneath the surface aloofness—the aesthetics of unapproachability—there lies a kind of hopecore. It is the ideology of the one boo, no ex T-shirt. As influential zillennials approach their 30s, they grow into an appreciation for the mundane and wholesome—the lifestyle of the downwardly mobile middle class.

Respectively, the middle-class origins of dandyism reflect (or are reflected in) its relationship to political engagement. What unites both types of dandies—just as cute and dark aesthetics coexisted simultaneously—is a shared disillusionment with politics and activism. Middle-class academia feels the moral urge to remain tapped into both political and cultural discourse; Dandyism, by contrast, retracts from that realm in favor of persona mastery. Politics remain irrelevant unless they obstruct rampant individualism and freedom of expression, which are currently more than encouraged by the status quo.

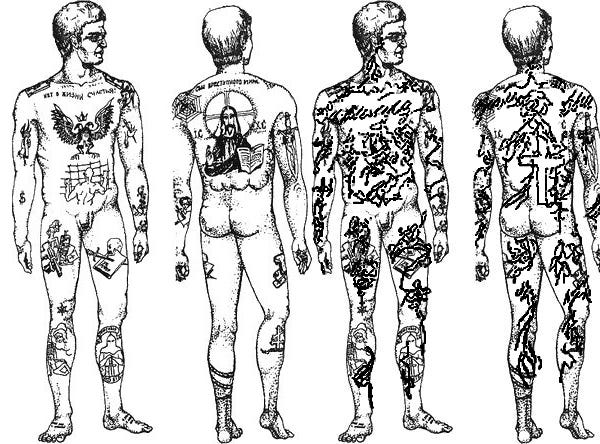

The body of a dandy must be a king of the kingdom of one, looking good with or without robes. Sad Dandy aesthetics are a part of massive boom in the tattoo culture. Fashion accessories extend beyond fabric, reaching the skin itself. The body is decorated, with or without garments. The end times are worn like a sleeve. Trauma becomes inscribed on flesh. The loss of meaning is not due to its unimportance, but because it obstructs form. And what form communicates is that nothing matters. There is nothing to say. Even if spoken aloud, meaning remains elusive because 1. it is private and 2. it is part of an image, which mirrors the dilemma of whether one truly believes in the sincerity of godposting.

There are multiple ways to interpret today’s youth lavishly investing in tattoos, endlessly layering them on top of one another. A psychological reading might suggest that the pain of tattooing serves as a means of processing internally stored traumas. In a way, tattoos are a safely inflicted self-harm, mediated through a third party—eventually blooming into the decoration of one’s flesh prison.

The body becomes synecdochic for the social system. 8

The other reading may be rooted in material reality. According to Joel Kotkin, not only is upward mobility increasingly constrained, but the acquisition of land and property is slipping out of reach. Another symptom of neo-decadence is the piggy bank shattered each month, snack culture at its finest. Too poor to buy property, too impatient to save, neo-feudal times offer solace in new clothes and new tattoos.

Certain tattooers take the path sad dandyism to an extreme. You book them through DMs, show up for the appointment. The tattooer is late. Needs to finish a cigarette. The design is found on Pinterest or crudely drawn. The work is done poorly, nonchalantly, with minimal hygiene. No aftercare. No attention to healing. No attention to detail. The finished tattoo is photographed badly and posted without a caption. It is middle finger to everything the industry once respected; punk gesture within an already punk community. Above all, it is an honest middle finger to a lifestyle of caring.

Both client and tattooer enter an exchange rooted in “whatever”—where, for a significant sum, you receive a poorly done tattoo that will fade in five years. This is the most lavish display of decadence possible. For dandies and their clients, appreciation is found solely in form—this is why fashion, luxury brands, and music seamlessly cross over with such a lifestyle. Clients admire the freedom made possible by hacking the system—off-the-radar cash transactions enabling travel, work, and a life unrestricted by traditional labor.

But this is only one side of the new wave of tattoers. The other is the sketch-like, experimental quality of the original drawings, which I actually consider amazing—something that classical tattoo culture had little space for. The shift of power and trust moves from client to tattooer, allowing for the sanctity of the body to be violated in the most expressive manner. If there is a biological concept that explains this, it must be the costly signal—a display of excess, wastefulness, and indifference meant to communicate status.

The sad dandy, part misanthrope, curates their appearance meticulously—yet chooses to communicate it through the signification of inaccessibility, distance, and detachment. The curse of the 2020s is knowing too much. Every gesture is judged, analyzed, read into—an ancient process of identity formation through borrowing, adjusting, internalizing, now accelerated. Quietness and detachment serve as both self-preservation and defense against the parasocial relationships waiting to form around you. To be a popular tattooer today, particularly in dandiacal circles, is to travel constantly, tattooing musicians and models as their private, secret provider. The mystery of the sad dandy is a protective shell against the dangers of sudden popularity in an unpredictable economy.

Distance also shields you from the emotional impact of your work being mistaken for someone else’s. This is especially common in the world of ‘research tattoos’—another subgenre of gothic, medieval, Pinterest tattooing, where designs are assemblages of various images pulled from the depths of the internet. To survive, you must develop a portion of your soul into a scammer—something your clients won’t mind. If anything, they’re equally eager to be scammed.

In the last four years, I’ve witnessed the rise of the generation of Kids With Guns —zoomers armed with an iPad, a Pen, and a Stencil printer (IPS for short), capable of tattooing anything they find online with minimal cost and minimal creativity. They are products of both skin-deep dandyism and the shrinking financial entry barrier into the tattoo industry. A good pen gun costs no more than $100. The chemicals and inks to tattoo moderately safely at home another $300. The bodies to practice on are free—tattoo-hungry friends always willing to lend their flesh.

And for dandylettes in their early 20s, there’s simply a lack of alternatives to make pocket money in a fun way. If you are already busy studying, why would you spend the whole day babysitting a brat for an hourly rate five to eight times lower than spending a chill afternoon at the studio, tattooing like-minded people?

"Tattoos are not forever," someone said to me during a session this year. They meant the endless possibility of blasting over them. A mind accustomed to excess will never know when to stop—because it doesn’t want to stop. The poetics of endless inscription seem not just like a contemporary addiction, but a perpetual curse.

As a tattooer, I cannot complain. The work has never been better.

The Endless Inscription

We’ve tried perfection, we’ve tried joy and now we’re embracing something more goth, more arcane.9

The social decay of perpetual end times naturally leads to aesthetics of austerity, marking a return to the Medieval and the Gothic. Cybersigilism, tribals, obscure medieval and gothic Pinterest finds all represent different variations of austerity in appearance. The key difference is shyness—small, ornamental, closed compositions versus large, open, crude sketches.

The fine-lined style is a response to the bulky, sticker-like tattoos of the past. Cybersigils, in particular, allow designs to stretch across large portions of the body, adjusting fluidly to the motion of a limb. They are meant to be built upon, layered over time. The quality of being unfinished is not just accepted, it is desired.

The sketch-like quality of the broadly understood fineline gothic —the most contemporary wave in tattooing—is a deliberate withdrawal from traditionally accepted notions of beauty. It is a design choice that exists in direct opposition to what your parents would have gotten in the '80s.

Symmetry and perfection are easily sacrificed for quick effect, for the beauty found in sultry crudeness of the design, the process, and even its documentation. The photos of girls, in turn, are curated into thirst traps for likes. Male bodies appear somber and tortured, sculpted into suffering. The hypermasculine and hyperfeminine qualities evoke images of a fallen crusader and a succubus superpredator, respectively.

The letters squeeze, tighten, and elongate into cathedrals, becoming unreadable. Their shapes grow spiky, wispy and hostile. The image loses its boundaries and fixed space, layering itself into oblivion. Meaning becomes obscured. The process of inscription never ends; it loops endlessly in a psychotic cycle of answers without questions. Form stretches over substance, casting a somber shadow. The image is temporal, fading by design. The decision to abandon the process was made both too soon and it was made too late.10

Going for the neo-gothic is an act of aesthetic rebellion against societal norms - the stigma, the employers, you parents opinion - as any subversiveness of Butler’s parody was back in the day.

If the sad dandy is to be placed within a tradition of thought, they would be Nietzschean. The Dionysian disruption, where he sees the potential of liberating a subject oppressed by institutions of power—such as family, academia, or the workplace — is to revolt against a signification process inscribed on the body by initiating a process of inscription oneself. The control over the body is taken back through putting money into a never-ending layering of meaningless forms, disappearing under each other, fading away with time, turning into a dandiacal impression of a lavish investment. What remains Dionysian is the mechanics of indulgence, but the revolutionary potential is gone. The neo-feudal system is fueled by self-love individual expression and can only be changed by sacrifice, which no one, will small exceptions, is willing to do. Endless layering in the affirmation of the self is the same narcissistic trap which Lasch has seen in the hippie movement.

Surface, surface, surface was all that anyone found meaning in . . .11

If the dandy were to be situated within a 20th-century aesthetic, it would align with that of the yuppie. The yuppie lifestyle, as fleeting as the Reagan Bull Market, marked a shift from an “aesthetic of externality” to a postmodern aesthetic of surfaces—an absolute fetishization of commodity, where commodification itself became a personal fetish.

Lee Gutkin also traces corresponding figures within 21st-century aesthetics. He publishes a book about dandyism in February 2020—right at the onset of the pandemic and concludes his historical study by turning to the contemporary, analyzing 10:04 by Ben Lerner and the figure of the "intellectualized hipster" portrayed in the novel:

The hipster is the cultural figure of the person, very possibly, who now understands consumer purchases within the familiar categories of mass consumption . . . like the right vintage T-shirt, the right jeans, the right foods for that matter—to be a form of art.12

Yet by the time he published the book in 2020, hipsterdom was already fading. No one was dressing like that anymore, and the term itself had been absorbed into everyday boomer vernacular, stripping it of its discursive relevance. Linking the hipster to the dandy was a means of illustrating -

dandy’s immaculate self-consciousness and disdain for sentimental effusions is perfectly attuned to the scholarly zeitgeist, allowing the critic to carve out a skeptical distance from the mainstream.13

The protagonist of 10:04 is labeled a hipster, but he could just as easily be called an overly intellectualized millennial, embodying the anxieties, tastes, and drives of his generation. Hipsters and dandies alike are subcultural members of the ruling class—this holds for both the happy and the sad dandy. Even if self-employed, their livelihood depends on social media popularity, making them a micro-nobility in the technofeudal infostructure. You might build a big enough following based on how creatively alternative you are, but, my God, you still work for Instagram.

The Epic Collage

There are shadows of cathedrals leaping across the backs of our decadent youth. The cathedrals are plentiful, their shadows overlapping into an endless collage, strokes layered like the marks of a whip on a martyr.

If there is a music genre of the end times, it is epic collage. Living in the perpetuity of a never-arriving collapse opens up space for endless layering. The remix culture reaches its peak in times that surpass subcultures, weaving aesthetics into a fluid interplay. This is the meta-part of the dandy—the par-excellence aesthete with a praxis.

In music, the endless layering of samples and genre-mixing originates in musique concrète and dub; today, it flourishes in a generation of young SoundCloud producers, crafting edits of insane creativity and sensitivity—more compelling than many original productions. Most of these tracks recontextualize pop and trap vocals, placing them over ambient, trance, or a mosaic of global drum patterns, taking the listener on an emotional, introspective journey.

Adam Harper, the critic who coined epic collage, closes his book by praising Burial for reaching “a level of subtlety and sophistication that transcends rave functionality and rewards close, thoughtful listening.”14 Alongside Mark Fisher, he indulges in endless praise of Burial’s ability to distill 90s rave ecstasy into modern sadness and nostalgia. The same nostalgia that once captivated Gen X critics is now resurfacing on SoundCloud as a (questionable) offspring of a single underground musician.

In 2014, Harper publishes System Focus: Adam Harper on the Divine Surrealism of Epic Collage Producers E+E, Total Freedom, and Diamond Black Hearted Boy, where he describes his epiphany upon discovering the music of Elysia Crampton—your favorite producer’s favorite producer. Elysia (now Chuquimamani-Condori) was among the first to blend the obscure and experimental with tender melodies of pop vocals into an ethereal realm of feeling just a little bit lost in life. Likewise, their blend of Frutiger Aero, native symbolism, and the tacky DJ graphics of the early internet saw a visual resurgence a decade later. Their deep cultural and emotional dedication left a signature on the grotesque excess of postmodern sampling, creating a new form of jouissance—one of feeling blue through a maximalist soundscape. The same love for rich textures can be found in contemporary producers like Hayden Kolb, Julek Ploski, Monker 178 or MASSI.

From this, we get epic collage—a genre that exists somewhere in post-irony, post-postmodernity, metamodernity, New Sincerity (or whatever name fits). The music says congratulations on being tapped in, but have you found love? It touches on romantic melancholy, infusing it with modern chaos and sonic insanity, extracting from the listener a deep sadness they didn’t even realize they had stored within.

The music to cry and dance to.

There are too many producers elevating pop vocals into club ethereal to name them all; one of them is Chickenmilk Dot Com, whose love for abundance of life runs deep through his music. His Elysian SFX are replaced by a highly rapid shifts in vocal samples and drum patterns—tracks that feel unpredictable, patchworked in a mysterious way. Melodies get chopped and screwed just when you start enjoying them too much. The love for pop vocals looming ambiently in the background must come from accessing the Divine Feminine—there’s no other explanation. I know for a fact that producers of this genre know all about Zodiac signs.

If there’s music that represents a scattered brain but a focused gaze, this must be it. Having befriended both Elly and Chicken, I can only say that beauty shines from a tender and curious heart, like diamonds in the sky.

Epic collage allows one to access a nostalgia for a past that never existed, or to experience the intensity of the end of the world with the brain accelerated to supersonic speed. The same speed that Baudrillard wrote about. The speed that “creates pure objects”—where the logic of desire collapses, because speed itself becomes a drive, annihilating longing in favor of movement for its own sake. These pure objects become “impossible objects” like music, which "has its own integrity, its own logic, its own history," as Harper puts it— as something to be experienced, not analyzed. The dandy cherishes this speed, because their persona is never complete, desire never fulfilled. The body is never sufficiently filled with tattoos, inexhaustible decorations.

The goddess basking in the moonlight at a secluded lake is not to be approached—not even admired from afar. The politics of dandyism are reclusive by nature, because every day, week, or month, the persona must be reinvented in private. The dandy is meant to be experienced, and the medium is the gaze. The dandy knows when they are being looked at—and in precisely what way the gaze is placed upon them.

The Death of the Dandy

In the final section of his book, Lee Gutkin describes the conditions of the 2020s that led to the emergence of both the happy and sad dandy:

One can imagine some version of post-irony that would permit a full-throated return to a confident aestheticism, an unabashed neo art for art’s sake.

He is not wrong in his materialist reading of post-irony; the post-Covid 2020s have produced a self-consciousness that, a decade prior, would have seemed like a “crack in the wholeness of [the dandy’s] nature”. Yet, over time, this self-consciousness has transformed into a circumstantial awareness—about politics, the status quo, the mechanics of the gaze, and the libidinal economy of becoming an icon. The dandy is fluent in culture.

The dandy exists as both a cultural and material phenomenon. The material prerequisite for dandyism is the living conditions that allow for the accumulation of goods, facilitating the endless remixing of self-creation—whether those goods are material or cultural.If there is one thing a dandy fears, it is the perishable cultural good—an entity that is rare, almost extinct in today’s world.

One of the cultural goods designed to be perishable was Agrippa (A Book of the Dead)—a 1992 collection of poems by William Gibson and Daniel Ashbaugh, released in both physical and digital formats. Its premise was that, upon exposure, the disk would overwrite itself, while the text in the book, printed on photosensitive material, would slowly begin to disappear. The slow disappearance, the loss of relevance is the dandy’s biggest fear.

Gutkin concludes his treatise on dandyism with his reading of the protagonist of 10:04 choosing to procreate in the face of the loss of meaning and the fear it invokes. For him, this ultimately anti-dandiacal act is the result of someone

disillusioned with disillusionment, aesthete who has become unsure about aestheticism. I am tempted to suggest that this uncertainty is the dandy’s terminus.

There comes a moment in life when everything has been lived through—all the weed has been smoked, all the sex has been had and the people met. When you have cycled through every aesthetic persona you ever imagined, when you have become Fernando Pessoa,—

I've dreamed of everything. There isn’t a single desire, no matter how strange or improbable, that I haven’t had – no, not one. […] All these lives I’ve lived in myself, with no need of gestures – without anything but the inner emotion of having lived them.15

But to be brave enough to face that in real life; then comes the absolute fear, the realization that you are perishable too, that the impressions you’ve made, the personas you’ve crafted, the aesthetics you’ve embodied—are all feeble in memory and will eventually fade.

The only solace is found in creation. And at the top of all creative acts, one old, conservative truth stands above all others—raising a child. A little copy of yourself who will relive you, who will, hopefully, stand by your bedside at the right moment, far in the future. I know only one tattooer and one tattoo couple who are raising a baby —a sweet, little Aloise. Shortly after the baby was born, they released T-shirts reading “RIP Lifestyle”—a tribute to their old studio, mistakenly taken as a farewell to their adventurous life.

Every death is a transformation—that is what the XIII Tarot card teaches us. There are no guillotines today, no emperor’s and empress’s heads lying at Death’s feet, but there is always the birth of new life—and the rebirth of the self, emerging from the reflection on who you are and how to live in harmony with others.

In back beat time I understand now

The joker and the ace and how to play my hand now

So when the lion doth roar I creep on by

And make another copy of the key to the sky16

There are no judgments to be made about either the happy dandy, the party socialite, or the sad dandy, the solitary figure retreating into the mundane. They do nothing but mirror the contemporary cope. But beyond them, there exists something greater—a good, old-fashioned selflessness, the ancient, almost forgotten way of wholly sacrificing oneself to a cause, bringing the end of the dandy and the end of individualism at large. A future I’d truly love for us to romanticize.

At that point, the culture will override itself, all the vibes will shift into one key-shaped force flinging open Heaven’s gate, through which an angel will push out a massive guillotine, adorned in gold, bearing the name Totaled Angelica, and the dandiacal heads will roll on the floor and the headless bodies will grab hands and dance among them to the music of excess, proudly wearing their 1993 Nike Decades.

Ben Dreith , Justin Isis Unveiled: On Neo-Decadence and the Literature of Anti-Apocalypse (2024).

Günseli Yalcinkaya, The Age of Innocence: When Did Everything Get So Cute?(2022) https://www.dazeddigital.com/life-culture/article/56132/1/cute-trend-drain-hang-bladee-marc-jacobs-heaven.

Allison P. Davis, "A Vibe Shift Is Coming. Will Any of Us Survive It?" (2022).

Barbey d’Aurevilly, On Dandyism, 44–45.

Coco Chanel in: Barnes, Interviews, 381.

Jess Cartner-Morley, ‘It’s game over for facts’: how vibes came to rule everything from pop to politics (2024) https://www.theguardian.com/culture/2024/dec/14/how-vibes-came-to-rule-everything-from-pop-to-politics?

Giulia Piceni, Why Medieval Fashion is The New Cool, https://imfirenzedigest.com/2024/09/27/why-medieval-fashion-is-the-new-cool/.

Judith Butler, Gender Trouble (1990).

Elizabeth Goodspeed, Heralding the ancient and otherworldly charm of Future Medieval graphics (2024) https://www.itsnicethat.com/articles/elizabeth-goodspeed-column-future-medieval-graphics-graphic-design-150824?

From my ‘post-esoteric luck medley‘ post on Substack.

Patrick Bateman in American Psycho (2000).

Mark Greif. Against Everything: Essays. Pantheon, 2016.

Felski, Rita. The Limits of Critique. University of Chicago Press, 2015.

Harper, Adam. Infinite Music: Imagining the Next Millennium of Human Music-Making. Zero Books, 2011.

Pessoa, Fernando. The Book of Disquiet. Translated by Richard Zenith, Penguin Books, 2002.

Murderous Joy by Carter Tanton.

The fundamental flaw in the analysis isn't the celebration of performative sadness, which I agree is interesting in itself, but your reliance on Kotkin's outdated neo-feudal narrative that positions tech figures as modern aristocracy, when their window is clearly passing. We can witness their descent into becoming merely the most visible prisoners of the same system, where, far from being puppet masters, these figures now frantically perform their own version of dandyism—Zuckerberg's new drip rebrand, Musk's increasingly strange Twitter stunts, and Bezos's space-cowboy aesthetics all reveal not oligarchs in control, but men increasingly captured by the same demands as the techno-serfs with Pinterest tats, differing only in scale and resources.

Jeepers